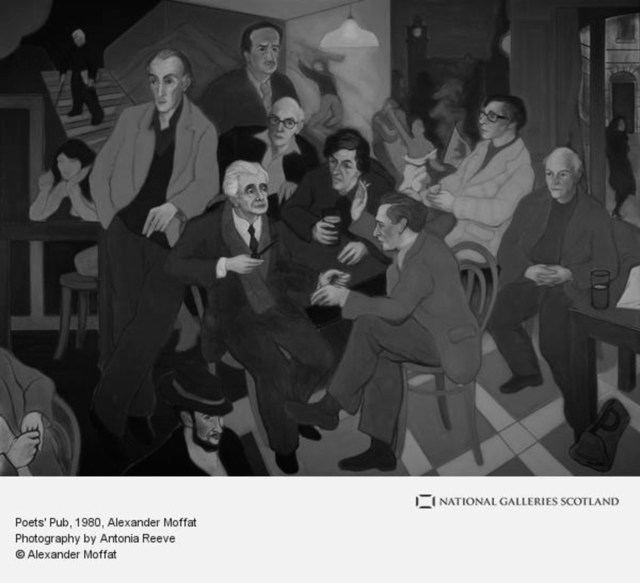

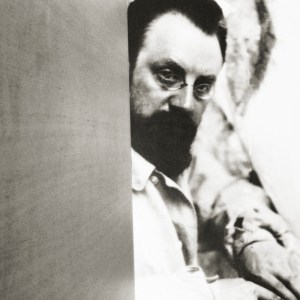

There is a painting in the National Gallery of Scotland by Alexander Moffat called The Poet’s Pub.

It was created in 1980 and features Norman MacCaig, Sorley MacLean,Ian Crighton Smith, Hugh MacDiarmid, George Mackay Brown, Edwin Morgan, Sydney Goodsir Smith and Robert Gariock.

A grand constellation of Scotlands poetic stars of the time.

It’s possible, if you fancy breathing the air around some of the landscapes which were important to the characters in this painting, to use it as a travel guide through some of the most fascinating places in Scotland.

If you’re looking at the painting you’re in Edinburgh where Sydney Goodsir Smith lived after his family moved from New Zealand and it was here that Robert Garioch was born.

A short hop east and you’re in Glasgow with Edwin Morgan.

If you head north and reach Orkney you can spend time with George Mackay Brown before heading south to visit Norman MacCaig in Assynt and Sorley MacLean around Skye.

You might call in on Ian Crichton Smith who lived in Oban for a while before reaching the centre of the painting.

Here, in the middle, Alexander Moffat places Hugh MacDiarmid as the fixed point around which the other poets circulate and Hugh MacDiarmid can be found in Biggar.

A warning should be applied to any travel based on romantic notions from the past, however. It might still be possible to enjoy history and heritage by visiting castles and gardens, but when it comes to exploring what it was in the landscape that energised poets to write about it, things get a little more tricky.

And when it comes to politics, as it so often did for MacDiarmid, the social landscape might be changed beyond recognition.

Of all the poets gathered in Alexander Moffat’s painting perhaps only George Mackay Brown might still be smiling in the 21st Century. His love was the story of Orkney, the saints, the Vikings, the tradition and the continuity.

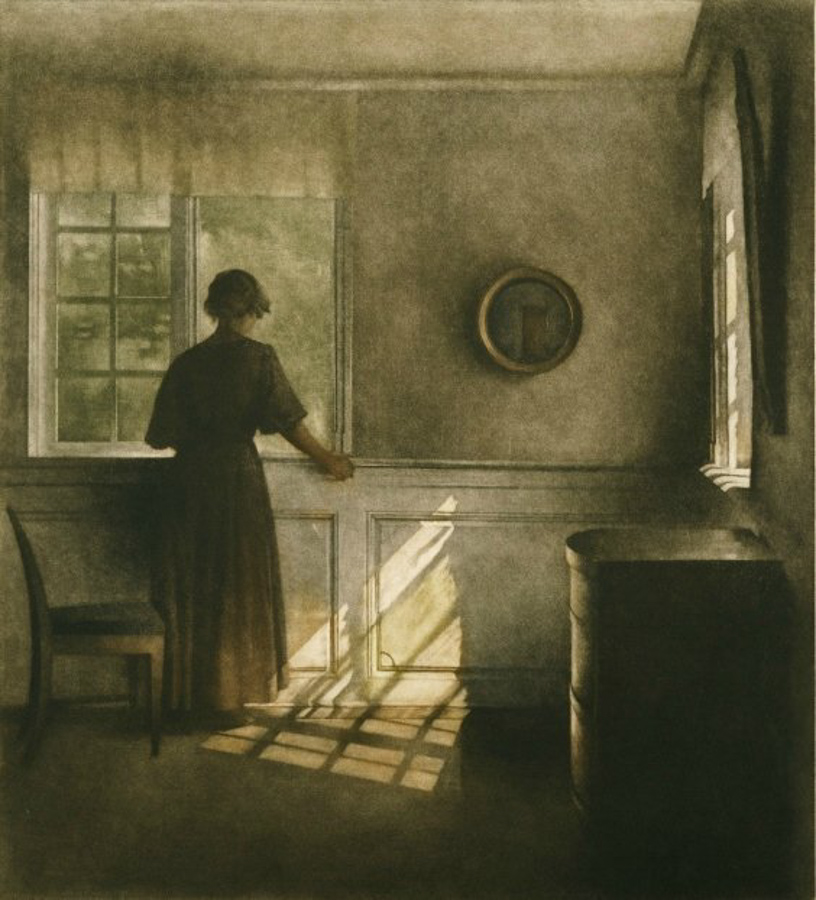

Stromness. The end of terrace house where George Mackay Brown was born in 1921 and the apartment (upper left) where he died in 1996.

Those things are an industry now but they are being explored in great detail and Mackay Brown would probably be fascinated. Their power and mystery are being enjoyed by thousands every year. The stories he told of his home place can be touched now and wondered at.

He might even have enjoyed listening to the tales of some of the tourists who stream from the cruise ships which lumber into Scapa Flow and clog the arteries of Kirkwall and Stromness.

He liked to listen to people over a pint but he would have to organise himself around the difficulty that his bar of choice, The Flattie, at the side of the Stromness Hotel, is closed and used now as a storage place for drones which might, one day, deliver goods from island to island across the archipelago.

The Stromness Hotel.

He would also have to come to terms with the fact that The Stromness Hotel is dry again despite his campaign in 1945 to introduce pubs into what was then a dry town.

What he might find more troubling is the popularity of Hoy.

The ferry to the island is booked days in advance and the onetime solitude of Rackwick is largely gone.

Mackay Brown and his friends, the painter Sylvia Wishart and the composer, Peter Maxwell-Davis, had a particular love for Rackwick. Maxwell Davis lived there because of its solitude.

Solitude and mass tourism are bad bedfellows.

The same phenomenon exists as you travel south along the west coast of mainland Scotland to Assynt with the poems of Norman MacCaig in your hand.

MacCaig holidayed in Assynt with his family and was enthralled by it.

Stac Polliaidh. Assynt.

Before he began to stay at Inverkirkaig, MacCaig spent summers in Achmelvich which is reached down a steep single track road terminating at a beautiful white sanded crescent beach.

A hut used by children as a big nature table full of drawings and shells and rocks once stood in front of the beach on an open space of grass.

Today, people play volley ball and light fires on that beach and the children’s shed is gone.

There has been a campsite at Alchmelvich for some time but it has expanded and has become much more popular. The problems with drainage in such a remote area are hinted at by smell here and there.

The land which runs down to the beach is a building site just now. The infrastructure of a very large car park, along with another campsite to join those which are already there and the North Coast 500 Pods which service travellers along that ever more busy route, is under construction.

The scars of building work will heal over time but what remains will welcome more and more people. The access is still steep and single track.

In 1967 MacCaig wrote, in ‘A Man In Assynt’;

‘Who possesses this landscape? –

The man who bought it or

I who am possessed by it?’

The question is, now, much more difficult to answer.

The man who bought it has developed it and thousands of people, every year, will find beauty in it, but not all of them are likely to have the same emotional connection MacCaig experienced.

It’s difficult to deny that tourism has, to a large extent, adversely affected the intrinsic lure of these remote places.

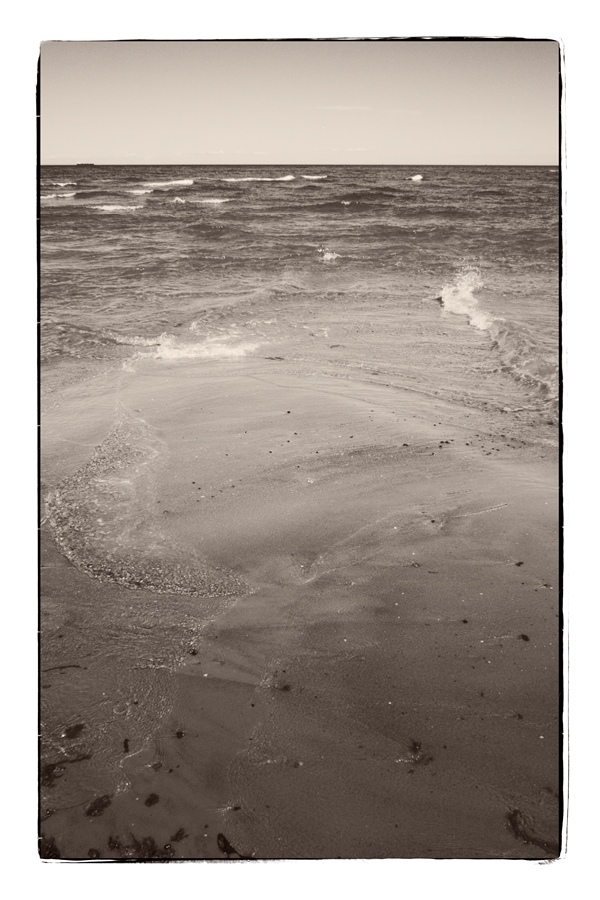

Achmelvich, Assynt.

MacCaig was a city man, working and writing in Edinburgh, who visited a place which was so remarkable to him that it possessed him.

Sorley MacLean lived and worked inside the landscape which possessed him. Born on Rassay and living in Skye and Plockton, he knew the landscape intimately.

Sorley MacLean’s house, Plockton.

His poetry, written in Gaelic, penetrates deep into what was once an isolated place over which he laid international concerns.

The bridge connecting Skye to the mainland consigned that isolation to history and, like Hallaig, MacLean’s famous deserted Rassay village, the old was swept away.

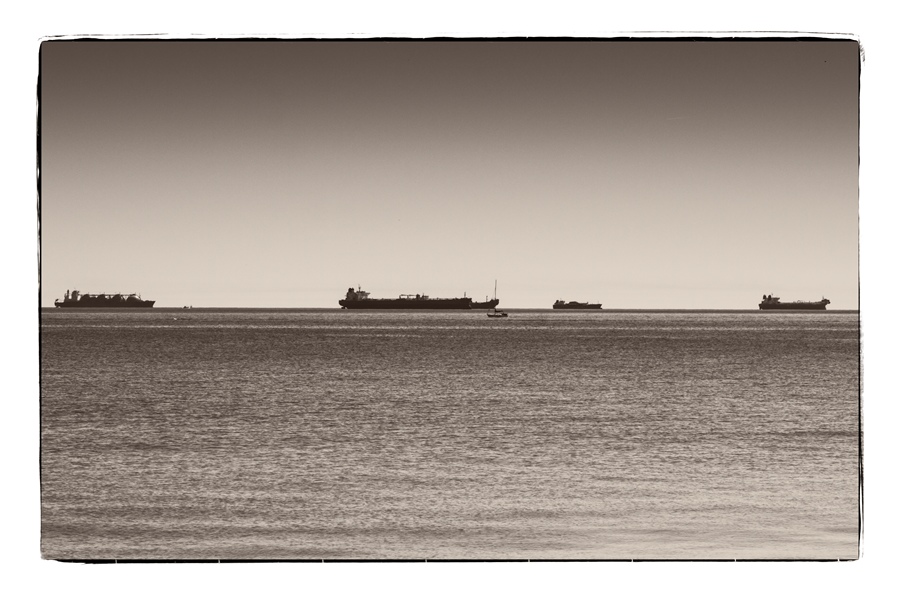

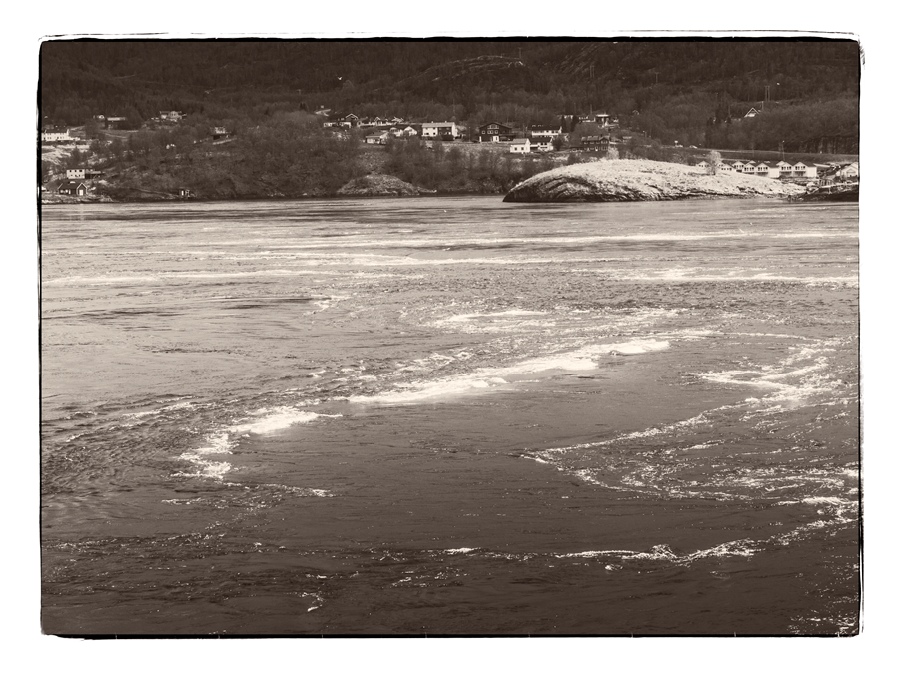

Rassay from Skye.

There may be a stark economic truth in the argument that without the income generated by tourism the northwest of Scotland would die.

Young people would leave through lack of work and decay would be inevitable.

Progress is built into survival and environmental compromise is the price.

So far the poets from Alexander Moffat’s painting might lament that what possessed them and enlivened their writing has been damaged by too much attention.

It’s only when you get to Biggar that your heart is saddened by the consequences of too little attention.

Until the onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020 Hugh MacDiarmid’s Brownshill cottage in South Lanarkshire was ticking over as a fitting reminder of this important writer.

Furniture and memorabilia left after the death of the poet and the later death of his wife, Valda, were still in place and a series of important writers’ residencies had taken place in the building.

Since Covid, and the drying up of appropriate financing, Brownsbank has slid into decay and decline.

A fine and energetic charity, MacDiarmid’s Brownsbank, has struggled to preserve the building and fund its resurrection.

For some reason this task has proved to be a steep uphill struggle.

If you stand by the little blue gate in front of Brownsbank it might be interesting to reflect on why there might be a celebratory George Mackay Brown trail in Stromness which speaks of his work and points out every feature in the town with any connection to the poet.

You could also smile at the pub in Plockton which has turned Sorley MacLean’s house into a B and B but, nevertheless, has placed a proud sign, ‘Sorley’s House’ above the front door.

You might scratch your head and wonder why Brownsbank, this major reference to Alexander Moffat’s central figure, is slowly disappearing.

MacDiarmid was hugely important to what became known as the Scottish Renaissance which sought to imbue modernism with a particularly Scottish cultural flavour.

It celebrated traditional influences and addressed Scotlands declining use of regional languages.

Under his given name, Christopher Murray Grieve, he began an exploration into a language form known as Synthetic Scots, or Lallans, built from regional languages together with words culled from Jameson’s Dictionary of the ScottishLanguage from 1808.

Norman MacCaig was fond of saying that Chris Grieve plunged into Jameson’s dictionary and Hugh MacDiarmid came out of the other end.

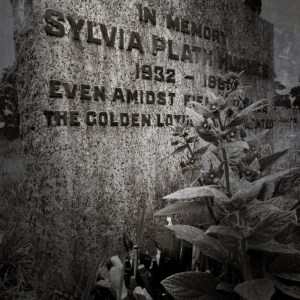

MacDiarmid became a major player on the international stage and visitors to Brownsbank ranged from Seamus Heaney to Allen Ginsberg. Yevgeny Yevtushenko visited with his girlfriend and MacDiarmid met and compared missions with Shostakovich.

By any standards he was an important artist. To many he was a Titan who was the most important Scottish poet of the 20th Century. In fact he is widely seen as the most important Scottish poet since Burns.

But – he was outstandingly difficult as a political thinker and he did think about politics a lot.

That he wrote not one but three long poems entitled ‘Hymn to Lenin’ indicates that he was never going to inhabit safe middle ground.

He had a brief flirtation with Fascism which, until the rise of Mussolini, he felt had considerable left wing potential.

He had an unfortunate record of saying that a German victory in the war might not be as bad for Scotland as continued English dominance.

He, at various times, championed Communism and Nationalism. He was co-founder of the National Party of Scotland from which he was expelled because of his Communist sympathies and he was a member of the Communist Party for whom he stood as Parliamentary candidate against Conservative Prime Minister Alec Douglas- Home in Kinross and Western Perthshire during the 1964 election.

He was expelled from the Communist Party because of his nationalist sympathies.

Following his political thoughts is like riding a rollercoaster but at every twist and turn they are imbued with a deep and revolutionary humanity which challenges everyone to try harder to make the most civil, and proudest, civil society possible.

Burns too, a not too distant neighbour in Dumfriesshire, penned lines which navigate towards a better way of being.

When he looked toward a time when … ‘Man to Man the warld o’er shall brithers be for a’that…’ his sentiments were taken to hart, chipped into stone and memorialised alongside the carefully preserved places where he was born, farmed and died.

There are statues to be found in odd places where he might have stopped to think and there might, one day, even be a route to the site where he disturbed a mouse.

When you get to Biggar, you might take some lines from MacDiarmid’s ‘Drunk Man Looks At The Thistle’ from 1926 with you…

‘And let the lesson be –

to be yersel’s,

Ye needna fash if it’s to be ocht else.

To be yersel’s –

and mak’ that worth being’

No harder job to mortals has been gi’en.’

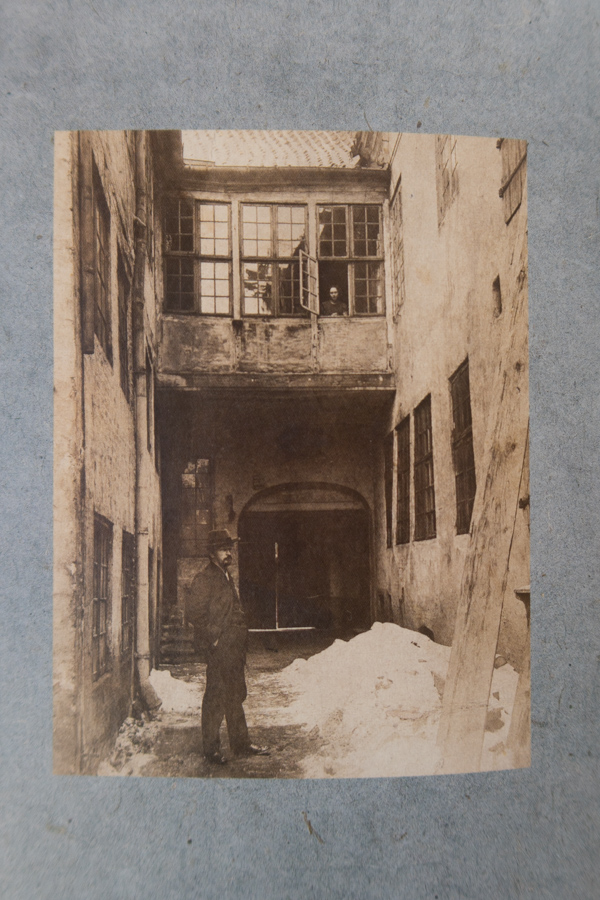

Chris’s Room (Christopher Murry Grieve). Thanks to MacDiarmid’s Brownsbank.

Chris’s Room 2024.

Valda’s Room, (Valda Trevelyn Grieve). Thanks to MacDiarmid’s Brownsbank.

Valda’s Room 2024.

There is an irony to be found these days in Alexander Moffat’s painting. The artists in The Poet’s Pub who circle that central figure are, by and large remembered and celebrated whilst a fitting memorial to the centre of the painting decays.

The atmosphere around Brownsbank radiates a quiet forgetfulness whilst the landscapes which some of the other poets drew upon have changed beyond recognition.

For some too much attention, for others, not enough attention.

Dinna fash yersel ower much, but the whole clanjamfrie’s worth the thocht. (It’s worth looking up.)

Let no tongue whisper here.

Between those strong red cliffs,

Under that great mild sky

Lies Orkney’s last enchantment,

The hidden valley of light.

George Mackay Brown … Rackwick

Glaciers, grinding West, gouged out

These valleys, rasping the brown sandstone,

And left, on the hard rock below – the

Ruffled foreland –

This frieze of mountains, filed

On the blue air – Stac Polliaidh,

Cul Beg, Cul More, Suivent,

Cansip – a frieze and

A litany.

Norman MacCaig … A Man In Assynt

‘Time, the deer, is in the wood of Hallaig’

The window is nailed and boarded

Through which I saw the West

And my love is at the burn of Hallaig,

A birch tree, and she always has been

Between Inver and Milk Hollow

Here and there about Baile-chuirn:

She is a birch, a hazel,

A straight, slender young rowan.

Sorley MacLean … Hallaig

It requires great love to read

The configuration of the land,

Gradually growing conscious of fine shadings,

Hear at last the great voice that speaks softly,

See the swell and fall upon the flank

Of a statue carved out in a whole country’s marble,

Be like Spring, like a hand in a window

Moving New and Old things carefully to and fro,

Moving a fraction of flower here,

Placing an inch of air there,

And without breaking anything.

Hugh MacDiarmid … Scotland